One of the main areas where I was never satisfied with Junkships procedural planetary generation was the generation of convincing looking gas giants and cloud systems on earthlike planets. I got some initially passable results by tweaking simplex noise, and adding some approximations of vortices as described here, but it never looked that great due to the fact that cloud formation is a highly physical process involving wind, temperature, pressure, and a bunch of other phenomena rooted in pysical simulation.

It was always my plan to revisit this part of the system and to add some amount of fluid simulation when generating cloud layers. With that said, my goal was not to accurately model the actual physics, but to build a lightweight simulation that would give a good final result, and run fast.

After reading up on the current state of the art I came across a great article here which proposed a really simple method that looked like it should tick all the boxes I was looking for. While this proved to be broadly true, there were however a number of isssues I had to overcome in order to get a satisfactory solution.

The TL;DR of the technique is that you generate a heightmap using a noise function (in my case simplex noise), calculate a vector which is the gradient of the noise field at each point, then rotate that vector 90 degrees around an axis defined by the normal. This set of rotated normals is your ‘flow map’. You then take your input texture and your flow map and move every texel in the input by the vector in the matching texel of the flow map - if you do this repeatedly the input texture looks as if it is a fluid flowing according to the hills and valleys in the original height map.

There is at least one other implementation of this technique out there (Heres some good slides by the developer of Space Nerds In Space) but I haven’t seen any that use the GPU to do the work. The advantage of using the GPU is that computing the flow calculations for a texture can be done dozens of times per second as opposed to minutes per texture iteration with CPU based implementations. This means that its possible on a mid range PC to generate gas giants or cloud layers within a second or two which is in keeping with my goal of having all asset generation occur near instantaneously at runtime.

There were a few problems with the technique as presented in the original paper, the main one being that it is designed to work in 2 dimensions, whereas I needed to generate the flow map on the surface of a sphere. While ‘rotating’ a vector by 90 degrees in two dimensions is pretty trivial, its not so obvious what this means in 3 dimensions. For those whose linear algebra is a little rusty the solution is:

- calculate the normal at the position on the sphere

- calculate the tangent at the position on the sphere (you could also use the binormal/bitangent instead)

- calculate the normal from the heightmap at the same position on the sphere

- calculate the cross product of the tangent and heightmap normals

or in HLSL

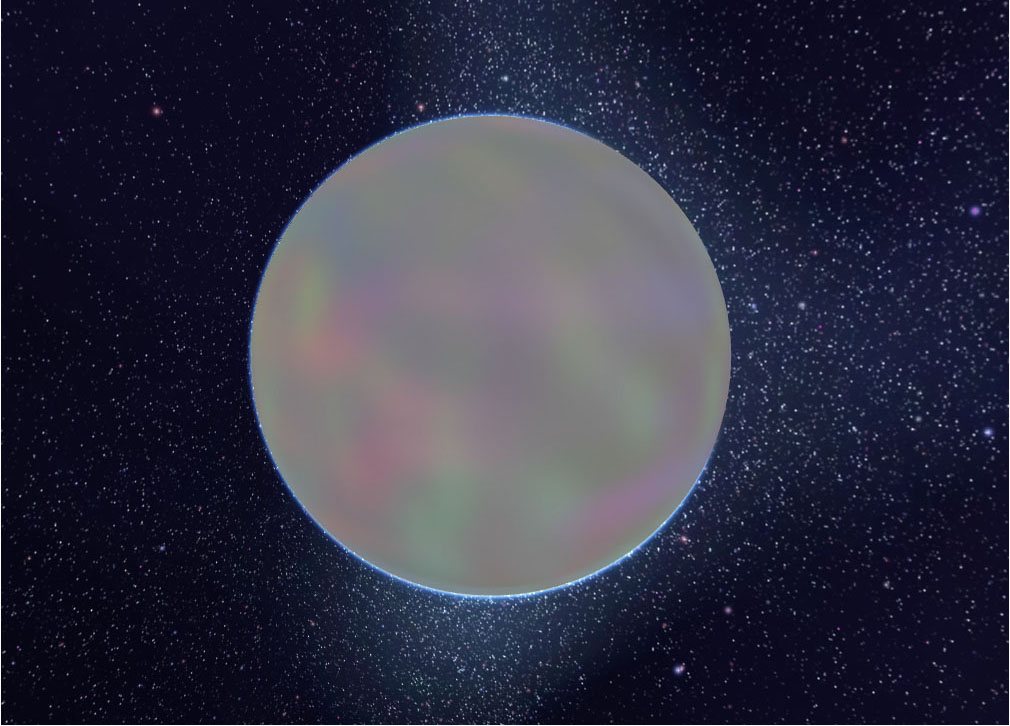

float3 flowVector = cross(input.tangent,heightmapNormal);This generates a flowmap with a smooth contour of vectors that can be stored in the rgb components of a texture as shown below.

The second problem with the technique is that it is effectively like putting the input texture into a blender, if you run enough iterations, all the original input colors will become evenly distributed and blended together. Because of this, its important to ensure that there is a limited number of flow iterations in order to allow for some mixing - but not too much. The problem with this is that the animation of the flow process looks really cool and it would be a pity to have to use a static version of a texture which is supposed to be showing cloud systems which should change appearance over time.

My solution to this was to split things into 2 stages - the first is the iterative blending process where each output texture is then recombined with the flow map. Once a number of iterations have been run. Once this has been done we have an input texture that can be used as the input to the second stage.

The second stage still involves the use of the flow map to warp the input texture, but importantly the output is not used as the input to the next frame (to prevent excessive mixing over time). Instead, the same input texture is used on each frame, and the flow map is rotated by a fixed amount. This gives the appearance of some dynamic fluidity when rendering, but ensures that the appearance of the texture remains consistent over long periods of time.

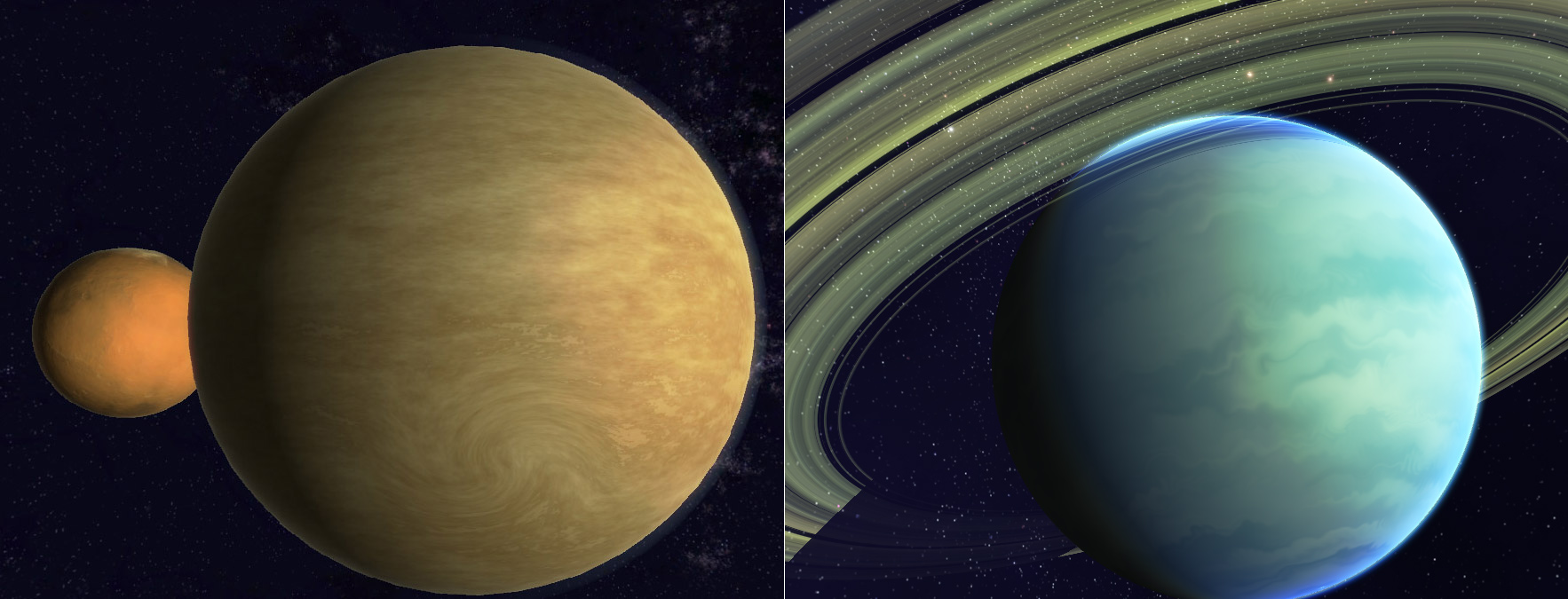

Gas giants: Old technique vs New technique

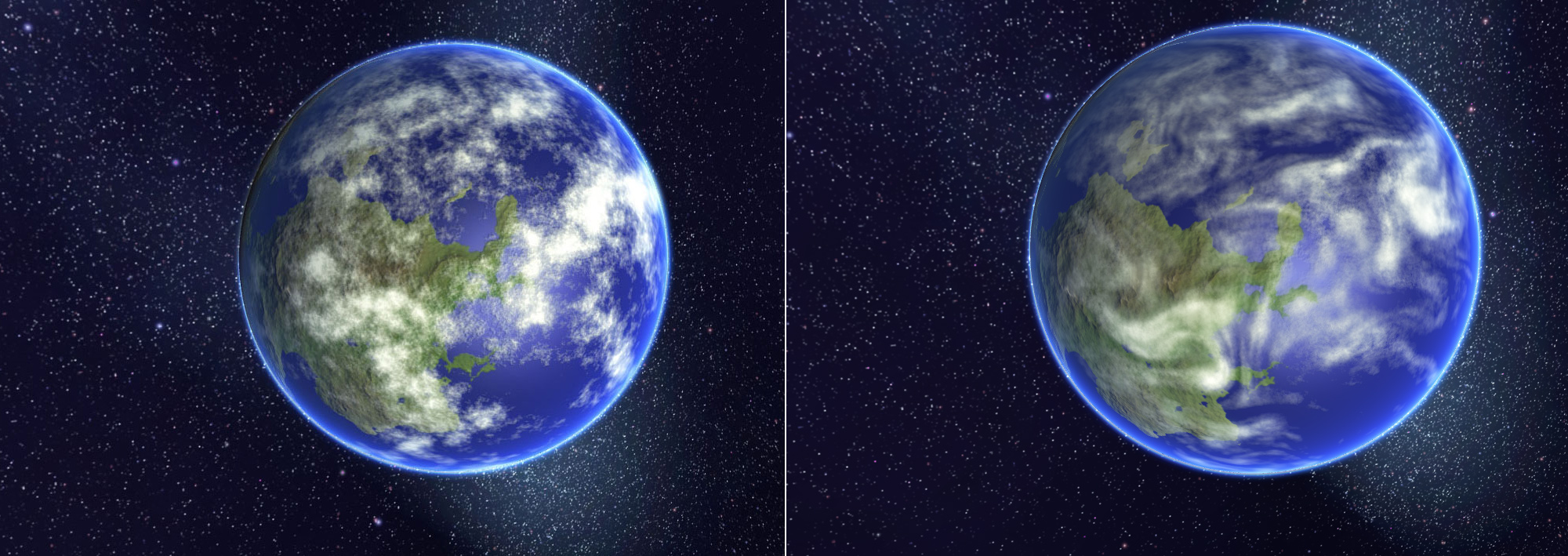

Clouds: Old technique vs New technique

As you can see the new technique gives vastly superior results to what I was doing before, ands its also proven to be much easier to tweak the generation parameters to provide a more predictable range of good outputs.

In other news I am also planning on fully open sourcing the Junkship solar system generation codebase soon. There are a couple of reasons for this, the main one being that I no longer have any desires to build this out into a fully fledged game or otherwise commercial product, I’d much prefer to refocus it into what it is, which is a cool demo for procedural graphics techniques. Because of this there is no real need or advantage to keeping the code private anymore, I’d much prefer to share and see other game developers take advantage of and build upon the the stuff I’ve worked on. Theres a fair chunk of work that still needs to be done to tidy things up and finish off some of the generation code, particularly around lighting and color palette generation - but I’m hoping to get the code up on Github in the near future (Take that with a grain of salt though, my time estimates tend to run on something approximating Valve Time)