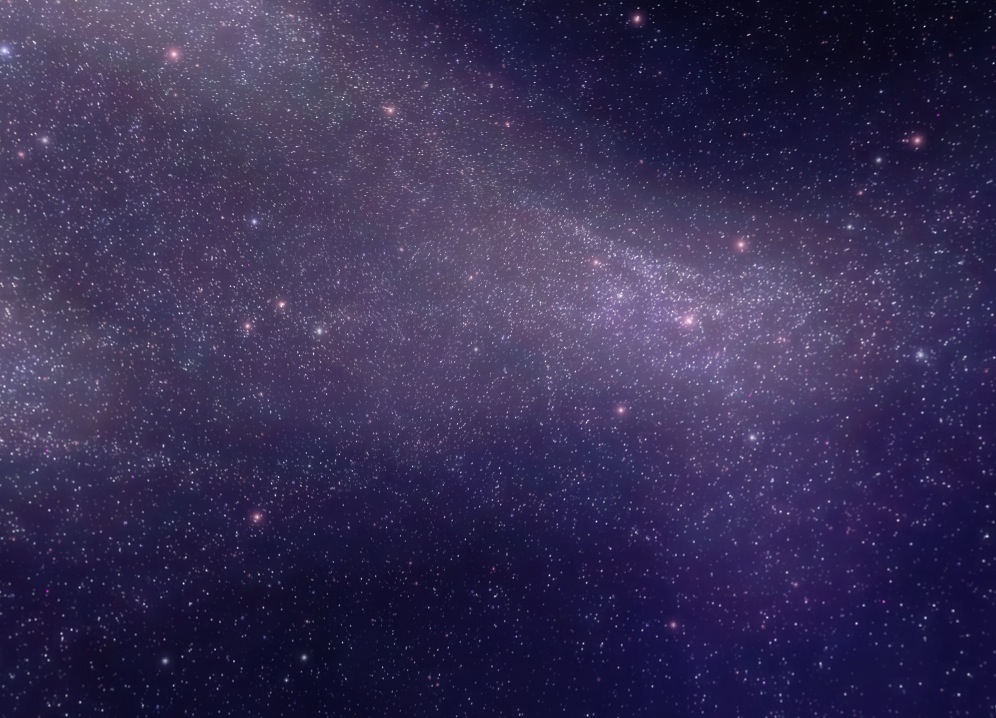

It has been a long time since I last worked on generating procedural star fields, but I was never particularly happy with the result that I came up with in my first attempt so when some time presented itself I decided to revisit the problem to see if I could come up with a better solution. It turns out I could, below is an example of what I came up with.

My original method (shown below) was largely based on combining successive layers of Perlin noise, and while this worked ok for the actual stars themselves it usually looked pretty terrible when it came to rendering nebulas and the gas and dust surrounding dense clusters of stars.

The reason for this is that star and galaxy formation is an inherently physical process, shaped by the gravitational interactions of billions of stars and giant clouds of gas and dust. The Perlin noise approach failed to take any of these physical factors into account and as a result it was extremely difficult to tweak it to get the relationship between star and gas density correct, and to get the overall shape and structure of nebulas looking convincing.

Because of this it seemed obvious that in order to get this right I was going to have to implement some sort of physics based particle system to at least approximate the physics involved. With this in mind I realized that given the number of particles that would have to be simulated (probably millions) that this was going to be impractical to do on the CPU and was going to be a job for the GPU if I wanted to keep the generation time to a minimum.

I ended up writing a Compute shader in which a large number of particles are simultaneously attracted to a handful of attractor particles which move randomly about 3d space. These attractor points are repositioned each frame on the CPU (as there’s only 2 – 3 of them ) and fed into the shader as a buffer. The shader then calculates the acceleration acceleration caused by each particle due the force of each attractor ( proportional to the square of its distance between the attractor and particle ) and updates the particles position.

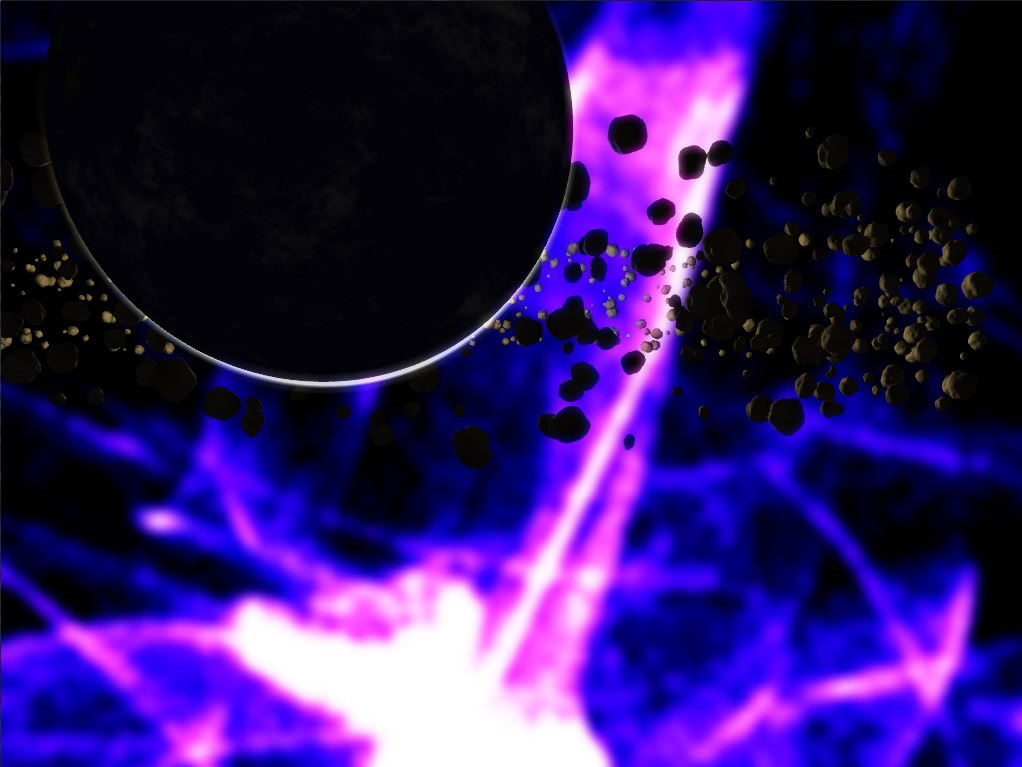

The effect of this is a very loose approximation to the force of gravity, but where all the particles can move independently of each other, making it extremely parallelizable. Having multiple attractors is essential in such a simple simulation as having a single attractor results in all particles converging toward a single point, whereas having particles being under the influences of multiple concurrent forces creates interesting and unpredictable patterns. Below is an early rendering showing around 1 million particles being simulated and rendered as point sprites.

Here’s the source code for the compute shader

cbuffer Constants : register(cb0)

{

uint GroupDimX;

uint GroupDimY;

uint MaxParticles;

};

cbuffer Physics : register(cb1)

{

float FrameTime;

uint AttractorCount;

};

struct Particle {

float3 CurrentPosition;

float3 OldPosition;

float3 Velocity;

float Scale;

};

struct Attractor {

float3 Position;

float3 Destination;

float Velocity;

float Strength;

float MinAttractorDistance;

};

RWStructuredBuffer<Particle> srcParticleBuffer : register(u0);

StructuredBuffer<Attractor> attractorsBuffer : register(t0);

[numthreads(1024, 1, 1)]

void main( uint3 dispatchId : SV_DispatchThreadID )

{

uint id = dispatchId.x + ( GroupDimX * 1024 * dispatchId.y )

+ ( GroupDimX * GroupDimY * 1024 * dispatchId.z );

//Every thread renders a particle.

//If there are more threads than particles then stop here.

if(id < MaxParticles){

Particle p = srcParticleBuffer[id];

float3 a = float3(0.0f,0.0f,0.0f);

for (uint i=0;i<AttractorCount;++i) {

float3 diff = attractorsBuffer[i].Position - p.CurrentPosition;

float distance = length( diff );

if ( distance <

attractorsBuffer[i].MinAttractorDistance ) {

// make sure particles don't appear inside an

// attractors min distance. If a particle

// gets inside the min distance, we'll push it

// to the opposite side of the min sphere

// This reduces large numbers of particles

// converging in a point around an attractor

float3 push = diff +

normalize( diff )

* attractorsBuffer[i].MinAttractorDistance;

p.OldPosition += push;

p.CurrentPosition += push;

}

a += ( diff * attractorsBuffer[i].Strength )

/ (distance * distance);

}

float3 tempPos = 2.0*p.CurrentPosition

- p.OldPosition + a*FrameTime*FrameTime;

p.OldPosition = p.CurrentPosition;

p.CurrentPosition = tempPos;

p.Velocity = p.CurrentPosition - p.OldPosition;

srcParticleBuffer[id] = p;

}

}The particle simulation when suitably tweaked came up with all sorts of interesting looking nebula type clouds, and worked well for rendering fields of stars. However as you can see in the screenshot above, even with a lot of blur applied to the particles, when rendering a cloud of point sprites they had kind of a lumpy appearance that gave away the fact that the cloud was actually composed of a finite number of particles. I tried all sorts of variations of increased blur, low pass filters, different particle sizes and shapes but the lumpiness was always present to some degree

It took me quite a while to figure out a solution for how to smooth out the particle field and I eventually figured it out after remembering an article I read about the rendering technique used to draw the skyboxes in Homeworld 2 (http://simonschreibt.de/gat/homeworld-2-backgrounds/). In that game the backgrounds were all vertex shaded using actual geometry which gave the backgrounds a very smooth almost painted look.

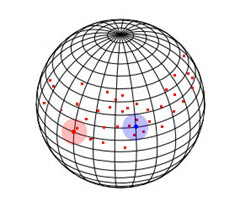

This got me thinking, could I use vertex shading to try and smooth out the rendered cloud? I started by normalizing all the particle positions so they sat somewhere on a bounding sphere with a radius of 1 unit. Then for each vertex on that sphere I summed up the number of particles within a certain distance and recorded that as the particle density at that vertex.

For example, in this image we can see that the vertex at the center of the red circle has a density of 1 as there is only one particle within the circles radius, whereas the blue vertex has a density of 4 as there are 4 nearby particles

The pixel shader can then render color based on this density, which the graphics card hardware will interpolate for us between the respective vertices for a smooth continuous output. Throwing all these ideas together gave me the following vertex shader (the pixel shader is trivial, it just renders a color whose opacity is based on the vertex.Intensity value and uses the normalized vertex.Velocity vector to lerp between two possible color values )

cbuffer ParamsBuffer: register(cb0)

{

float4x4 WorldViewProjection;

float MaxDistance;

int MinThreshold;

int ParticleCount;

};

StructuredBuffer<Particle> particleBuffer : register(u0);

Nebula_VSOutput main(VSInput input)

{

Nebula_VSOutput output;

float4 worldPosition = mul(float4(input.Position,1.0f),

WorldViewProjection);

output.LocalPosition = input.Position;

output.Position = worldPosition.xyww;

output.Velocity = float3( 0.0f, 0.0f, 0.0f );

int intensity = 0;

// find how many particles are within a threshold distance

// of this vertex

for (int i = 0; i < ParticleCount; i++)

{

Particle p = particleBuffer[i];

float distance = length( normalize( p.CurrentPosition )

- input.Position );

intensity += distance <= MaxDistance ? 1 : 0;

output.Velocity += p.Velocity;

}

output.Velocity = normalize( output.Velocity );

output.Intensity = saturate( ( intensity - MinThreshold )

/ (float)ParticleCount );

return output;

}Turns out it worked exactly as I had hoped! the rendered clouds were now perfectly smooth provided that the sphere used to render the skybox had a sufficient polygon count. It also had the ancillary benefit of requiring far less particles for an equivalently detailed cloud which helped reduce the simulation time. Below are a couple of different procedural star field renderings, each field is rendered after around 60 physics iterations and contains around 2 million particles for the point sprite stars, and around fifty thousand particles for the nebula clouds. A full skybox is rendered in 300 layers with one layer per frame ( so as to not adversely affect the frame rate of other rendering ) which ends up taking around 5 seconds.