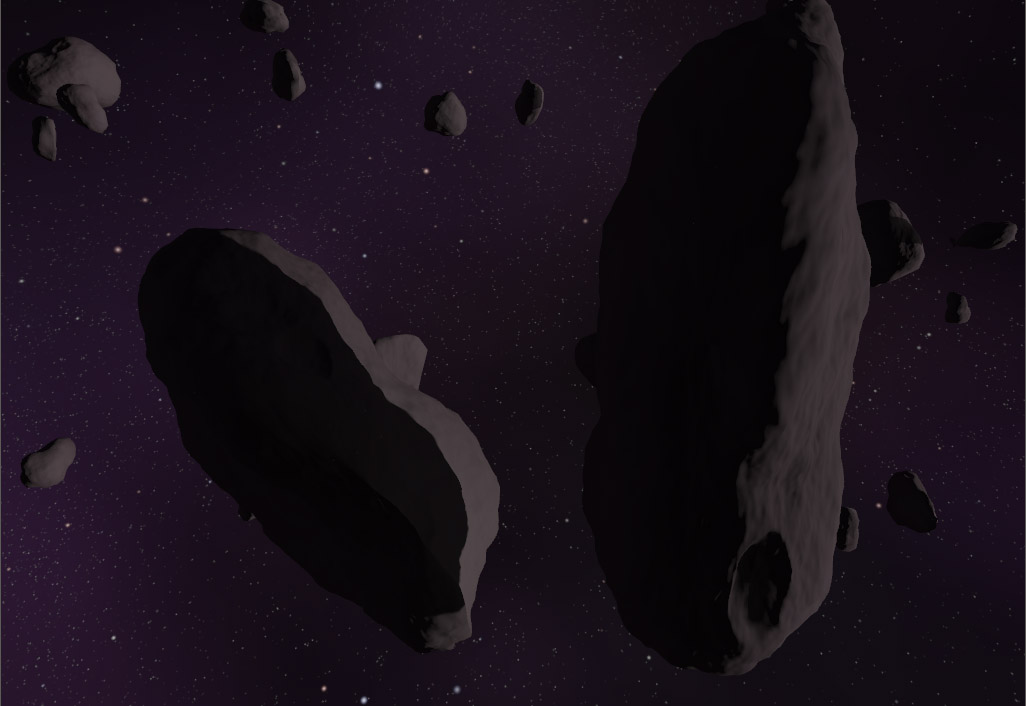

You might think that realtime shadows are a largely solved problem. Most games have them, and for the most part they look great - but this hides the fact that aside from some recent advances in realtime ray-tracing (RTX etc.) the state of the art for realtime shadown rendering is an ingenious, but in practical terms terribly flawed technique known as the shadow map. I knew eventually I’d have to build in shadowing support into my engine, but what I didn’t realize was that shadow mapping techniques are really optimized for usecases where your viewpoint is close to a solid ground plain with a directional lightsource projecting down from above. Space represents a really challenging environment as you don’t have any ground plain, you have a point light source (a star) - not a directional one, and there are potentially huge distances between shadow casters and shadow receivers.

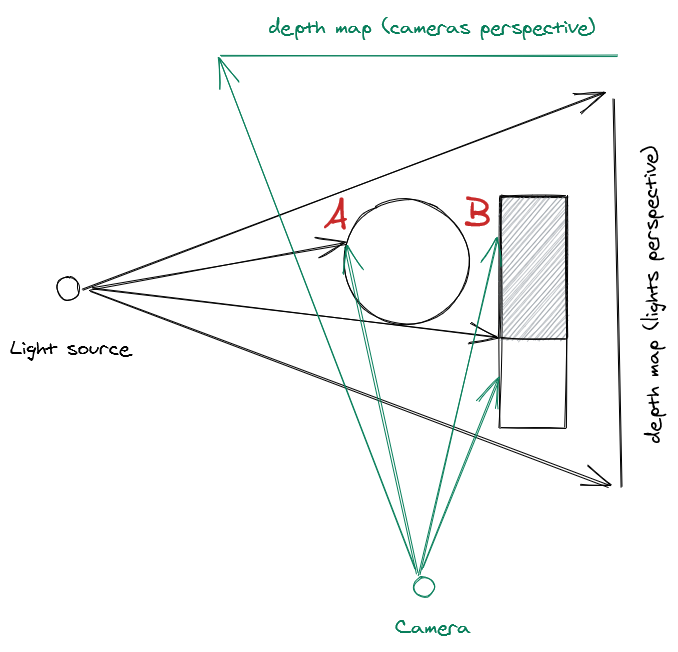

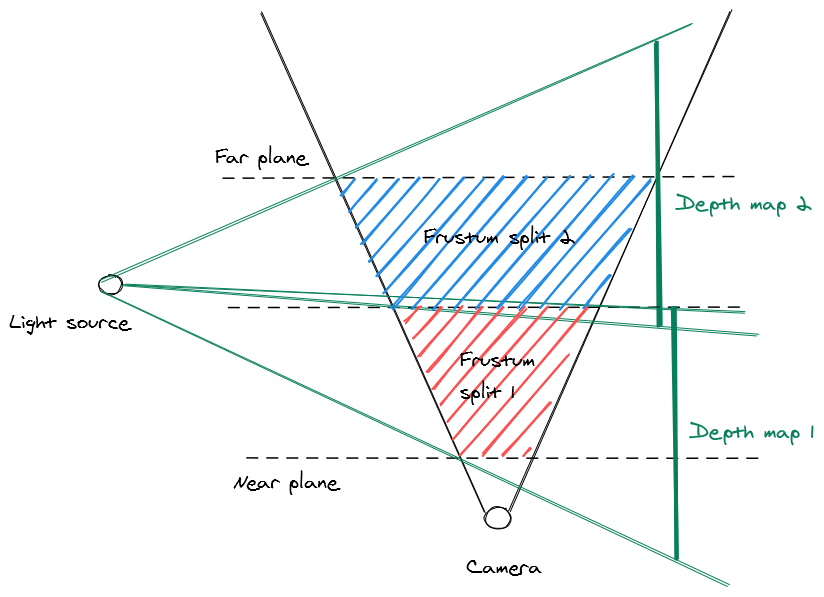

The basics of how shadow mapping works is shown in the diagram below. You render the scene twice, once from the perspective of the light source, and then once from the player camera. Each rendering of the scene records the distance from the source to the nearest piece of geometry, otherwise known as a depth map. Once these two depth maps have been calculated, we can determine which parts of the scene are lit or shadowed by calculating whether the distance from the lightsource at any given point is greater than or equal to the depth in the lightsources depth map for that given point. In the example below, point A is lit because the distance along the ray from the light is equal to the distance in the depth map, but B is in shadow because the distance along the ray from the light is greater than the distance in the depth map.

Soft shadows

The problem with classic shadow maps is that they cast hard edged shadows, and the accuracy of the shadows is dependent on the resolution of the shadow map, so over time a number of techniques have been developed to try and achieve higher quality and more natural looking shadows.

VSM - Variance shadow maps: These produce really bad ‘haloing’ or light-bleeding artifacts when you have overlapping shadow casters. In a crowded asteroid field, you frequently have more than one asteroid blocking a light source, so this is a non-starter.

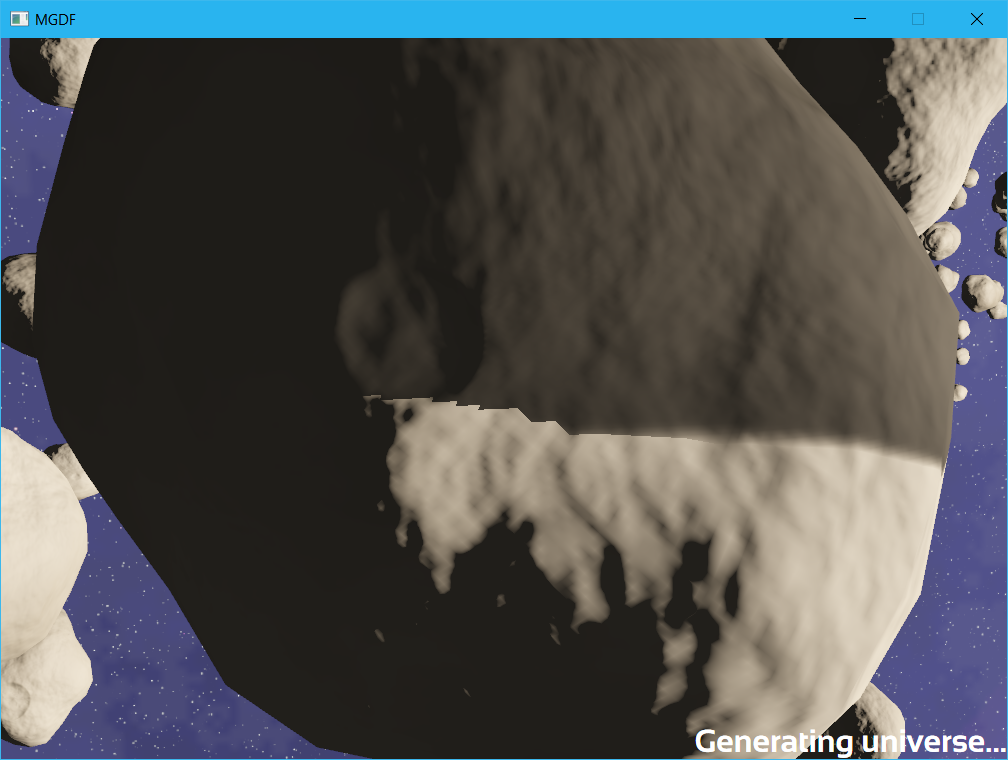

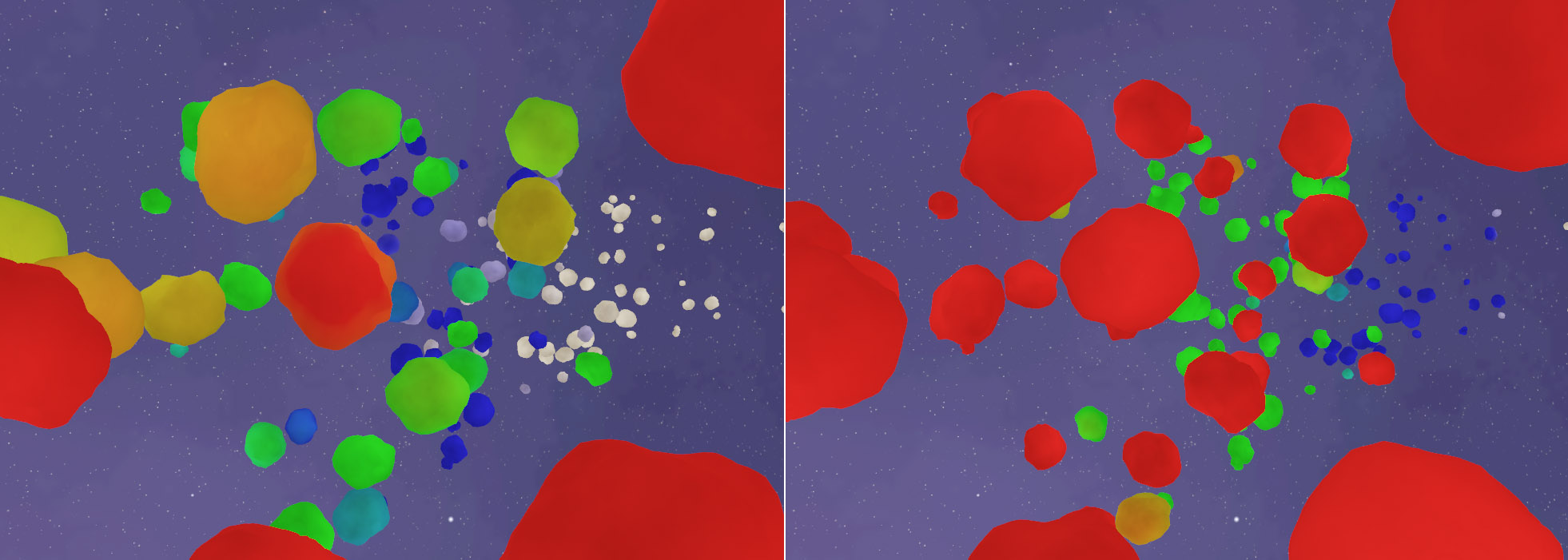

ESM - Exponential shadow maps: These have some nasty edge cases that as long as you have a ground plain and don’t have too many overlapping shadow casters you probably wouldn’t notice. In a space asteroid field, these assumptions are false much more often leading to frequent unsightly artifacts (see the image below for an example)

PCF - Percentage closer filtering: A brute force technique to just take multiple samples around a pixel and average the results to smooth out the edge of the shadows. While its not very elegant, its simple and gets the job done so thats what I ended up using

Shadow map resolution

The next problem you run into is that since shadow mapping is a screen space technique, the shadow map has a finite resolution, so you end up having to balance between the resolution of shadows & the draw distance of those shadows as the map has a limited amount of world space that it can cover and for a larger worldspace target, each pixel in the shadow map needs to cover a larger area leading to pixellated shadows. This is where most of the tweaking and hacks around effective use of shadow maps comes from - optimizing the space in the shadow map so that you get the best resolution for shadows close to the camera combined with an acceptable shadow draw distance.

Directional vs point lights

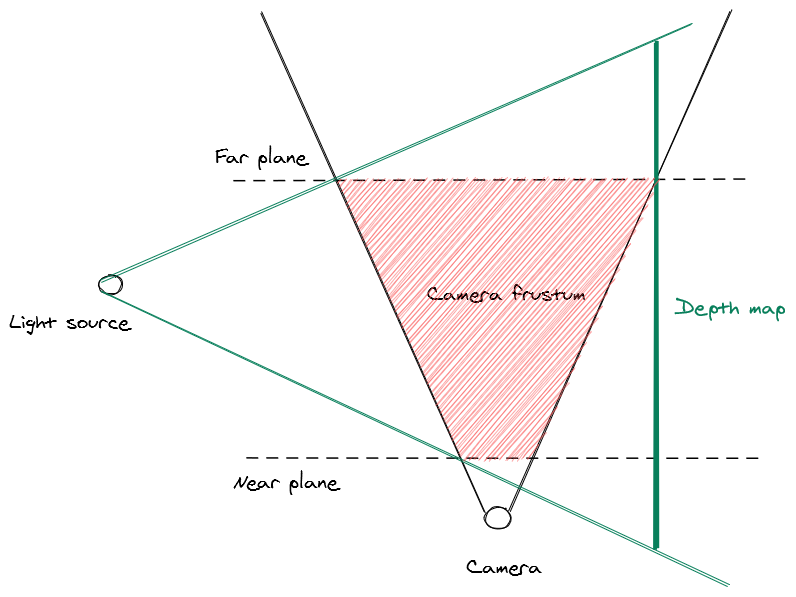

As I mentioned - most uses of shadow maps involve directional lights. The reason for this is that you can use an orthographic projection to render the shadow depth map, which results in a nice uniform resolution of the shadow depth map. Using a point light involves having to do a perspective projection of the depth map that results in higher resolution of shadow samples toward the center of the shadow map. Unfortunately in the kind of space environment I want to render we have a point light i.e. a star in the center of the solar system, so we have to use a perspective projection. Now to be totally accurate you would need to do a cubemap projection and get a depthmap from the stars position covering all possible viewer positions, but this is impractical as the shadow resolution would end up being far to low & you’d be rendering depth maps for objects that are so far from the viewer as to be non-visible anyway. So in order to increase the shadow map resolution to practical levels we cheat by only recording the depth map that lies within the visible area of the screen - known as the camera frustum.

This gives us the best use of our available shadow map space as we’re only rendering depth values for the area that covers the visible screen - however, even in this case the limited resolution of the shadow map means that up-close shadows still look very blocky. To fix this we can rely on another brute-force technique - known as cascading shadow maps (CSM). Just render a bunch of depth maps starting from a small one close to the camera and expanding in size along the view vector, then when rendering the shadows, pick the shadow depth samples from the highest available depth map at that point in the view space.

Because each cascade overlaps the others, we can get a bit of extra resolution by not partitioning strictly by the distance along the view vector, but by checking if the world space position hits a position that the depth map covered - that way we can aggressively prioritize using the closer & therefore more detailed shadow maps. Below is a comparison of which cascade gets picked (warm colors represent the highest detail cascades, & cooler colors represent lower detail cascades) under the two approaches.

Cascade strict distance vs aggressive

Theres also some art to picking how to split the cascades & how many to do - I use a logarithmic distribution, favoring more maps closer to the camera for better up close resolution at the expense of less detail further away & found 6 cascades to be a good balance between quality and performance. Below we can see an animation of the algorithm in action, picking different cascades as the camera moves through the scene.

Theres also another problem that this introduces, since the depth map is constantly moving along with the camera view, the shadows can appear to move or ‘swim’ when you move the camera. For this you have to go to some considerable lengths to ‘snap’ movement in the depth map vectors to whole texel multiples (i.e. you need to calculate the world space size of a texel at the point of the view vector and only allow the depth map source to move in increments of that - this doesn’t completely remove shadow movement (as perspective depth maps have non-linear texel sizes, but it keeps things largely stable in the center of the viewport).

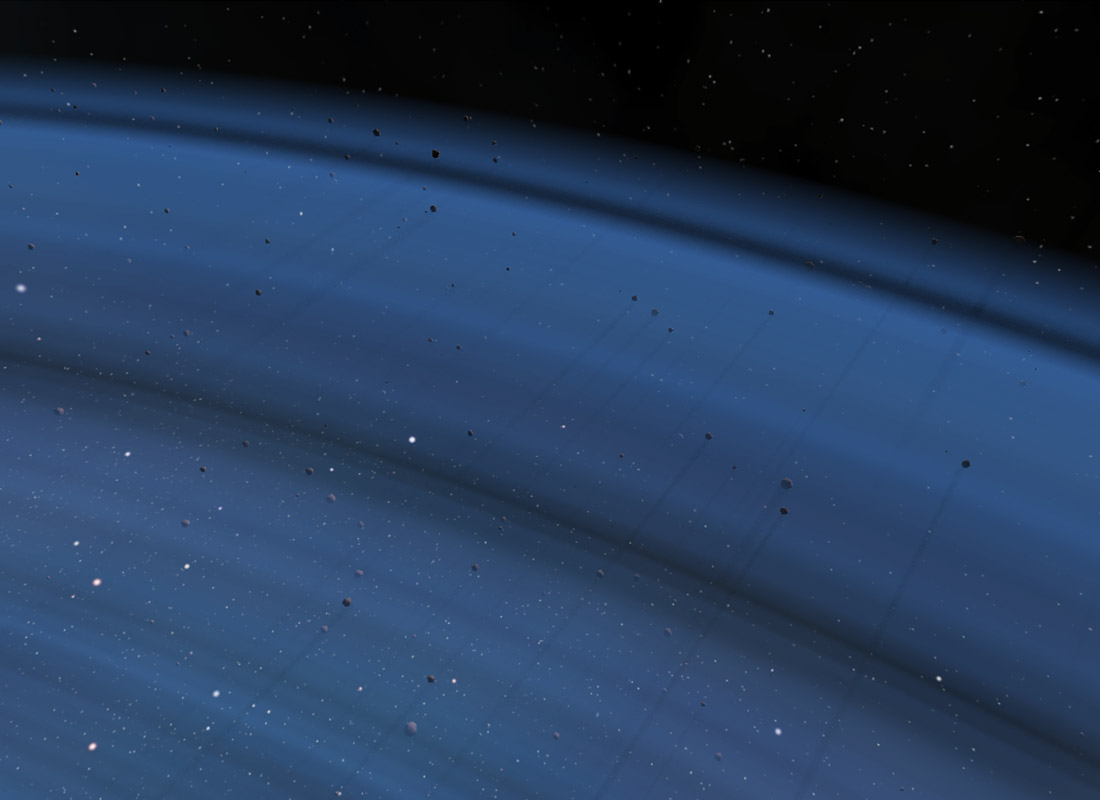

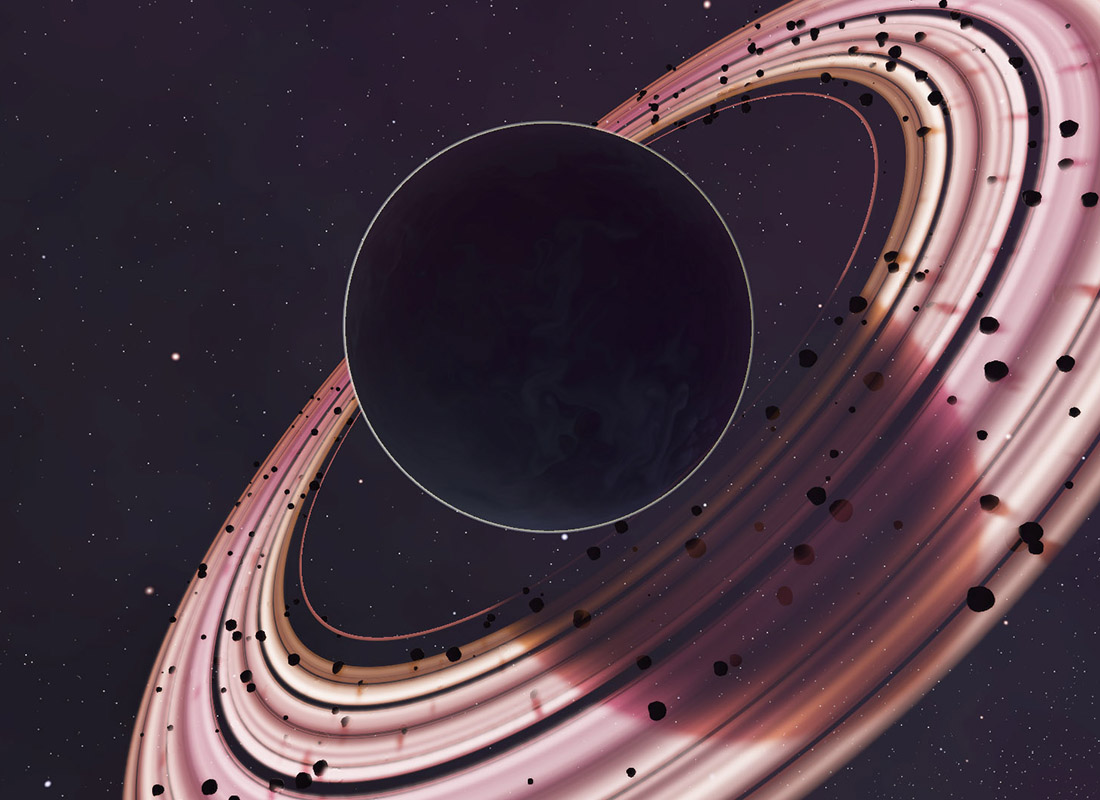

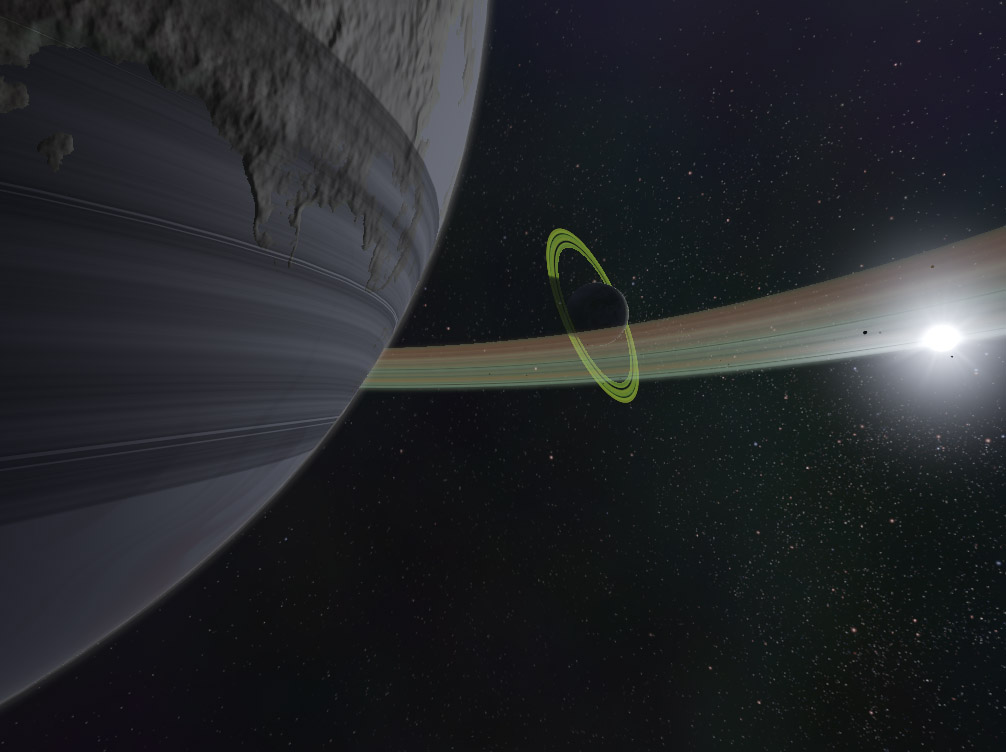

One nice thing about the shadow map is that is can be used just as easily for shadowing geometry as for volumetrics or particles. Shown below are shadows cast by asteroids onto volumetric fog used for planetary rings.

Geometric analytical shadows

All the hacks above get us to a point where we get pretty nice looking dynamic shadows for objects up close, but as things get further away the lower resolution of the shadow map makes them less and less effective. This is a problem in space scenes where there is typically very large distances involved and we don’t really want shadows from small objects like asteroids projecting gigantic shadows onto planets half way across the solar system. To solve this I decided to treat very large and very small objects as separate as far as the lighting and shadowing was concerned. And because the large objects have very predictable geometry I could come up with some very geometry specific shadowing techniques that allow for much better results than a generic technique like shadow mapping.

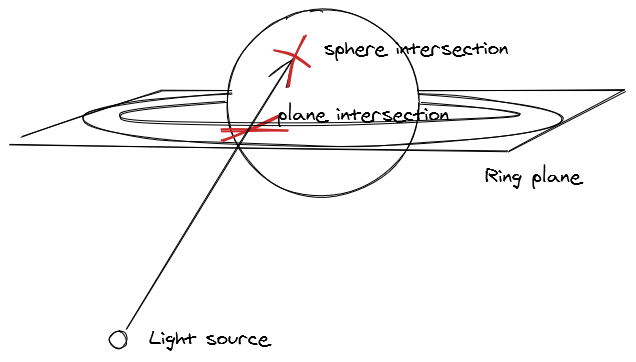

All planets are spheres & its mathematically relatively simple to do a vector sphere intersection test so you can analytically determine if any planet is in the shadow of any other planet. You can also determine the distance of the intersection from the center of the shadow caster sphere to the edge & can therefore trivially do soft shadows from any given planet to another.

Similarly the shadows on a planetary ring system can be determined with some basic geometry. In that case you want to see if the vector at any point in the ring plane passes through the planet sphere or not. Finally you can also cast shadows from the ring plane down onto the planet itself by doing a plane intersection test from a point on the planet sphere through to the lightsource, determine the radius of the intersection from the origin & then lookup the ring texture to see the alpha value of the ring at that point.

Combined these effects allow for a pretty convincing solution to the shadowing problems I’ve run into thus far, but the lesson here is that there isn’t really a good general case solution when using shadow maps, you’ll need to hack and tweak them (a lot) to get good results.

One unrelated thing I wanted to note: you might have seen it was 4 years since the last post. I have actually been working on Junkship during this time, just procrastinating to an insane degree when it came to writing posts. I tend to update more often with screenshots and videos on Twitter & have dabbled in streaming on Twitch, but I have a huge backlog of topics I’d like to write detailed posts on & I’m hoping that finally getting this published can help me get back into the rythm of writing more often. But who knows maybe it’ll be another 4 years :)